HPV and Warts Risk Assessment Tool

Answer the following questions to assess your risk of developing warts due to HPV exposure:

Enter your information and click "Assess Your Risk" to see your risk level.

Important Note: This tool provides general guidance. Consult a healthcare provider for personalized advice.

When you spot a small bump on your hand or foot, you might think it’s just a harmless skin tag. In many cases, those bumps are Human Papillomavirus (HPV), a common virus that also causes the skin growths we call warts. Understanding how HPV and warts interact helps you spot symptoms early, choose the right treatment, and take steps to prevent future outbreaks.

Quick Takeaways

- HPV is a family of more than 200 virus types; about 40 of them affect the skin and cause warts.

- Warts appear when HPV infects skin cells called keratinocytes and triggers rapid growth.

- Most people contract cutaneous HPV in childhood; the immune system usually clears it, but the virus can linger.

- Good hygiene, avoiding direct contact with existing warts, and using protective footwear reduce risk.

- Vaccines targeting high‑risk HPV strains do not prevent common skin warts, but they protect against cancers linked to other HPV types.

What Exactly Is Human Papillomavirus?

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a small DNA virus that infects epithelial tissues. It spreads through skin‑to‑skin contact, sexual activity, or, for the skin‑specific types, via tiny cuts or abrasions. The virus family is divided into two broad groups: mucosal types (linked to cervical, anal, and throat cancers) and cutaneous types (the ones that cause warts). Though the public often hears about the vaccine for cervical cancer, the same virus family is responsible for the everyday bumps many of us see on hands, feet, or even the face.

How Does HPV Lead to Warts?

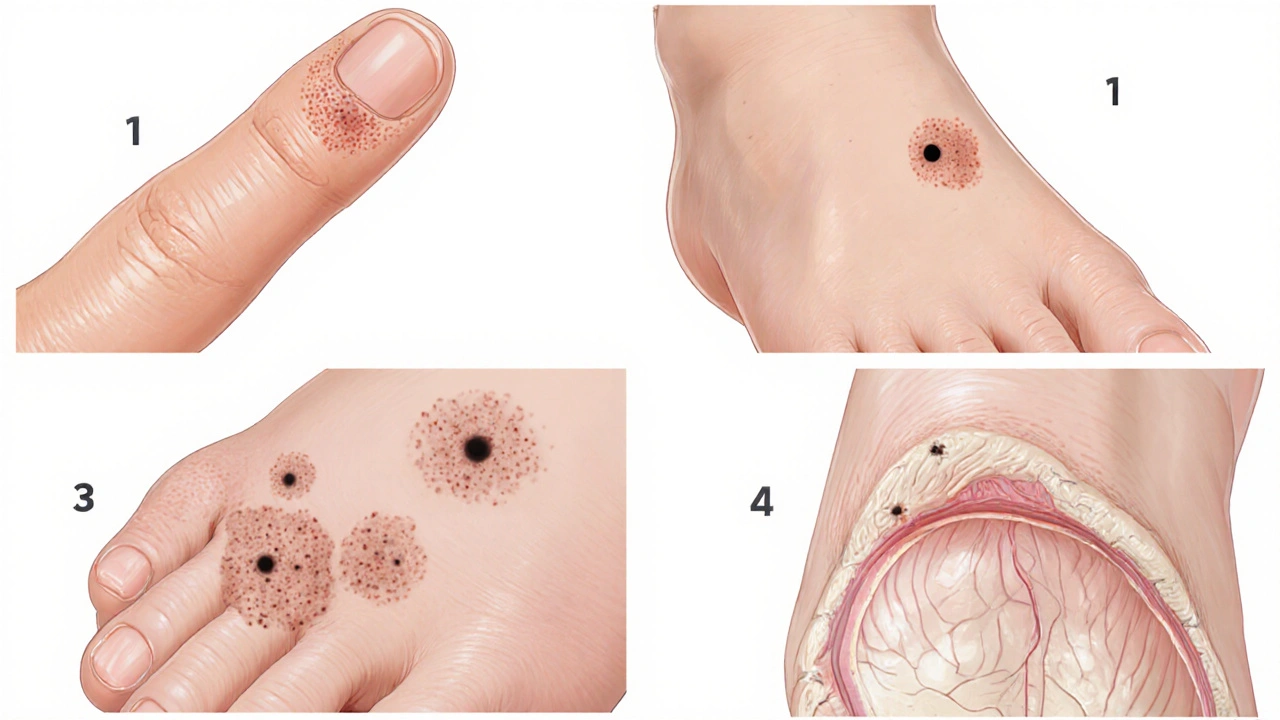

When a cutaneous HPV type lands on a break in the skin, it penetrates the keratinocytes-the cells that make up the outermost layer of our skin. The virus hijacks the cell’s machinery, causing the cells to multiply faster than normal. This uncontrolled growth creates the raised, rough texture we recognize as a wart. Different HPV strains produce distinct wart shapes:

- Common warts (HPV 2, 4) appear on fingers and hands.

- Plantar warts (HPV 1) grow on the soles of the feet and can be painful under pressure.

- Flat warts (HPV 3, 10) are smoother, often clustering on the face or legs.

- Genital warts (HPV 6, 11) arise in the moist genital region and are medically termed condyloma acuminata.

Who Is Most Likely to Develop Warts?

Anyone can get a wart, but a few factors increase the odds:

- Age: Children and teenagers have the highest exposure because they often have minor skin injuries during play.

- Weakened immune system: Conditions like HIV, organ‑transplant medication, or even a recent cold can reduce the body’s ability to clear HPV.

- Skin moisture: Damp environments (public showers, swimming pools) help the virus survive longer.

- Existing warts: Having one wart makes it easier for the virus to spread to nearby skin.

Diagnosing HPV‑Related Warts

Most warts are diagnosed visually by a dermatologist or primary‑care provider. When the appearance is ambiguous, a simple PCR test can detect HPV DNA from a small skin scraping. This test is especially helpful for genital warts, where confirming the HPV type guides treatment and informs vaccine counseling.

Treatment Options: From Home Remedies to Clinical Procedures

Most warts disappear without intervention, but many people choose treatment for comfort or cosmetic reasons. Options include:

- Salicylic acid: An over‑the‑counter keratolytic that softens the wart’s outer layer. Apply daily for several weeks.

- Cryotherapy: A dermatologist freezes the wart with liquid nitrogen, causing the tissue to slough off.

- Immunotherapy: Topical agents (e.g., imiquimod) boost the local immune response to clear the virus.

- Laser ablation: Precise laser beams remove stubborn warts, especially on the face.

- Cantharidin: A blister‑inducing compound applied by a clinician; the wart lifts off after a few days.

Choosing a method depends on wart location, size, number, and patient preference. Discuss potential scarring or pain with your clinician before proceeding.

Preventing Future Outbreaks

Because HPV lives on the skin’s surface, simple hygiene habits go a long way:

- Keep cuts clean and covered until healed.

- Avoid sharing towels, socks, or personal grooming tools.

- Wear flip‑flops in communal showers and pool areas.

- Wash hands frequently, especially after touching a wart.

- Consider regular skin checks if you have a weakened immune system.

For genital HPV, the HPV vaccine (Gardasil9) protects against the most common cancer‑causing strains (6,11,16,18,31,33,45,52,58). While it does not prevent the skin‑type warts discussed above, vaccination reduces the overall viral load in the community, indirectly lowering transmission risk.

When to Seek Medical Attention

Most warts are harmless, but certain signs warrant a professional look:

- Rapid growth, bleeding, or ulceration.

- Pain that interferes with daily activities.

- Warts appearing in the genital area or spreading quickly.

- Multiple warts appearing after a recent illness, suggesting immune suppression.

Prompt evaluation helps rule out rare complications, such as malignant transformation of long‑standing HPV lesions on the hands (a condition called squamous cell carcinoma in situ).

Key Differences: Cutaneous HPV vs. High‑Risk HPV

| Aspect | Cutaneous HPV (Warts) | High‑Risk HPV (Cancer‑linked) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Sites | Skin of hands, feet, face | Cervix, anus, throat, genitals |

| Common Types | HPV 1,2,3,4,10 | HPV 16,18,31,33,45,52,58 |

| Health Impact | Benign skin growths; occasional pain | Premalignant lesions; cancers |

| Vaccine Coverage | Not covered by current vaccines | Covered by Gardasil9 |

| Diagnostic Test | Visual exam; optional PCR | HPV DNA test, Pap smear, HPV‑specific PCR |

Living With HPV: Myths and Realities

Many people mistakenly believe that a wart means they have a sexually transmitted infection. That’s not true for the common skin‑type HPV strains. Only the mucosal strains associated with genital warts and cancers spread through sexual contact. Another myth is that once you get a wart, you’ll always have it. In reality, the immune system can suppress or eliminate the virus, and warts often vanish on their own within two years.

Final Thoughts on the HPV‑Wart Connection

Knowing that warts are a visible sign of a harmless skin strain of HPV demystifies a common concern. While the virus can linger, good hygiene, timely treatment, and, where relevant, vaccination keep the risk low. If you notice a new skin bump, especially after a cut, consider a quick check‑up. Early action can prevent discomfort and stop the virus from spreading to others.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can warts turn into cancer?

Typical cutaneous warts caused by low‑risk HPV types rarely become cancerous. However, long‑standing lesions on the hands of immunosuppressed patients can sometimes develop into squamous cell carcinoma in situ. Regular monitoring by a dermatologist is advisable if warts persist for many years.

Is the HPV vaccine useful for preventing common warts?

No. The current vaccines target high‑risk mucosal HPV strains (like 16 and 18) and the low‑risk genital strains (6 and 11). The cutaneous types that cause everyday warts are not included, so the vaccine does not prevent them.

How long does it take for a wart to disappear after treatment?

Treatment response varies. Salicylic acid may need 4‑12 weeks of daily use. Cryotherapy often clears a wart in 2‑3 sessions spaced a few weeks apart. Some warts resolve faster, while others may require multiple rounds of therapy.

Can I get warts from someone else’s wart?

Yes. Direct skin‑to‑skin contact with an active wart can transfer the virus, especially if the skin is broken. Avoid touching warts, and wash hands thoroughly if you do.

Is it safe to treat warts at home?

Over‑the‑counter options like salicylic acid are safe for most adults when used as directed. However, if a wart is painful, rapidly changing, or located on the face/genitals, see a clinician first to avoid scarring or misdiagnosis.

I am a pharmaceutical expert with over 20 years of experience in the industry. I am passionate about bringing awareness and education on the importance of medications and supplements in managing diseases. In my spare time, I love to write and share insights about the latest advancements and trends in pharmaceuticals. My goal is to make complex medical information accessible to everyone.