Infectious Keratitis Treatment: What Works Best

If your eye feels gritty, red, and painful, you might be dealing with infectious keratitis. This condition is an inflammation of the cornea caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses or parasites. Ignoring it can lead to vision loss, so catching it early and starting treatment right away matters.

Common Causes and Symptoms

The most common culprits are bacterial infections from contact‑lens wear, eye injuries, or contaminated water. Fungal keratitis shows up after trauma with plant material, while viral forms often follow a cold sore outbreak. Typical signs include intense redness, blurred vision, tearing, light sensitivity and a white spot on the cornea.

Because each cause behaves differently, doctors will ask about your lens habits, recent travel, and any eye injuries. A quick slit‑lamp exam and sometimes a culture of the discharge help pinpoint the exact organism so you can get the right meds.

Effective Treatment Options

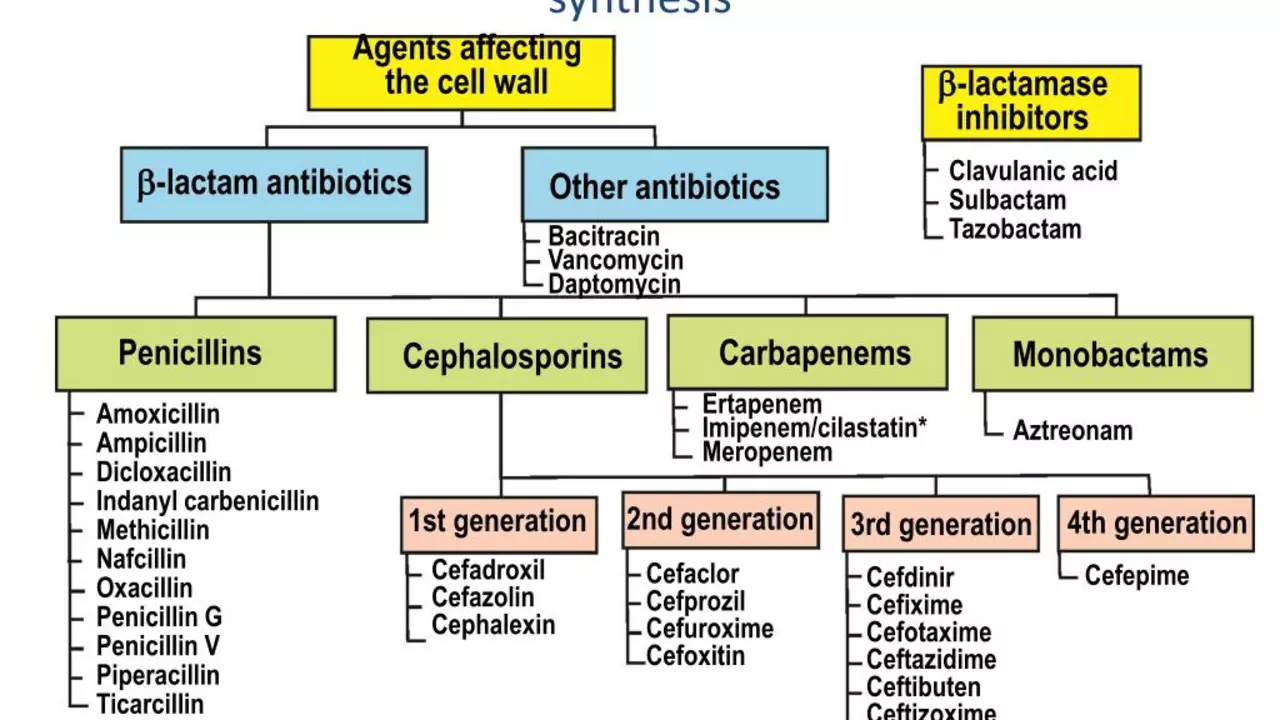

Once the infection type is known, treatment usually starts with prescription eye drops. Bacterial keratitis gets fortified antibiotics like cefazolin or tobramycin every hour at first. Fungal cases need antifungal drops such as natamycin or voriconazole, often for weeks.

If you have a viral infection, antiviral ointments like trifluridine are used, and oral antivirals may be added for severe herpes keratitis. For parasites like Acanthamoeba, a combination of biguanides (PHMB) and chlorhexidine works best.

In many cases, doctors will also prescribe steroid eye drops after the infection starts to clear. Steroids reduce scarring but must only be used under close supervision because they can worsen an active infection.

Beyond meds, keep your eyes clean. Use sterile saline washes, avoid rubbing, and stop wearing contact lenses until cleared. If you wear lenses, switch to a daily disposable brand and follow strict hygiene rules.

Follow‑up visits are crucial. Your eye doctor will check healing progress, adjust drops if needed, and watch for complications like corneal thinning or ulceration. Most patients see improvement within 3–5 days of proper treatment.

If the infection is advanced or doesn’t respond to drops, a procedure called therapeutic keratoplasty (corneal transplant) may be required. This is a last‑resort option but can save vision when medication fails.

Bottom line: act fast, get an eye exam, and stick to the prescribed drop schedule. Early, targeted therapy combined with good eye hygiene gives you the best chance for a full recovery without lasting damage.