Every year, over 300,000 women around the world die from cervical cancer. Most of those deaths aren’t inevitable-they’re preventable. The key lies in three simple, proven steps: vaccination, regular screening, and timely treatment. Yet, too many people still don’t know how HPV leads to cancer, or how easy it is to stop it in its tracks.

What Is HPV, and Why Should You Care?

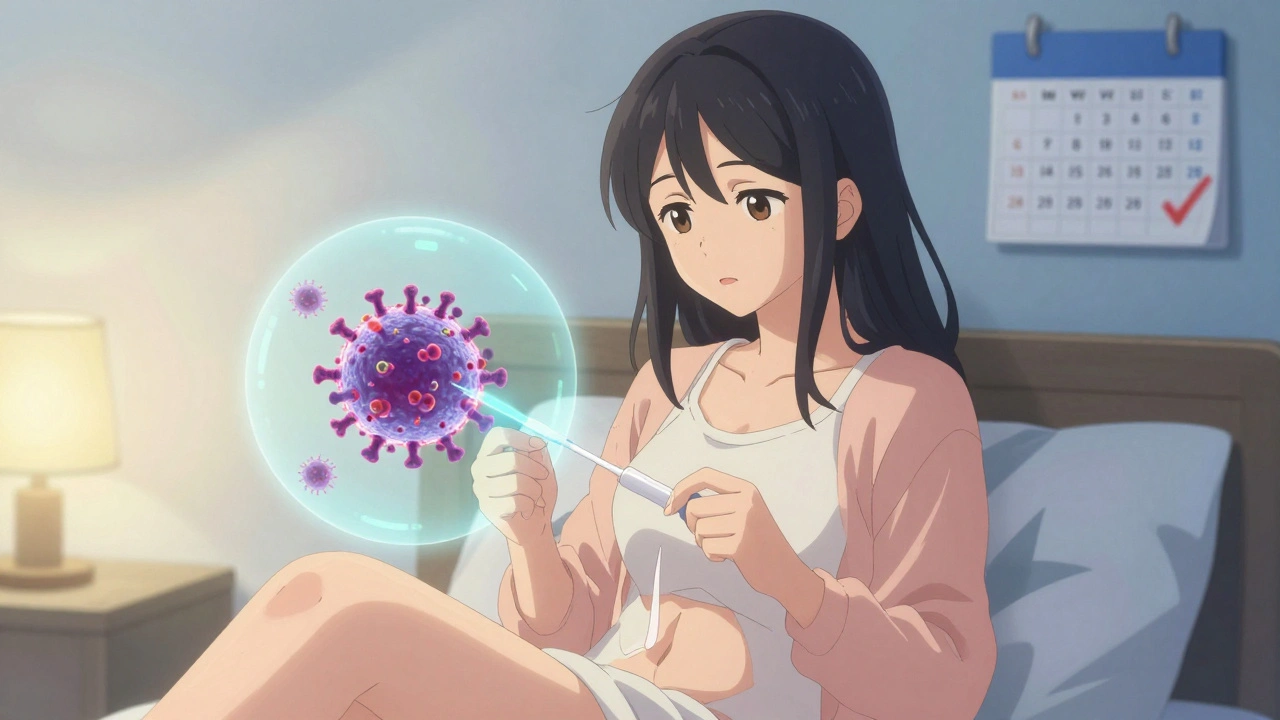

Human papillomavirus, or HPV, isn’t just one virus-it’s a family of more than 200 related viruses. About 40 of them affect the genital area. Most people will get at least one type of HPV in their lifetime. The good news? The body clears over 90% of these infections on its own within two years.

The problem comes from the high-risk types, especially HPV 16 and 18. These two alone cause about 70% of all cervical cancers. But HPV doesn’t stop there. It’s also linked to cancers of the vulva, vagina, penis, anus, and throat. These cancers don’t show up overnight. They grow slowly, over 10 to 20 years, from precancerous changes that can be caught and treated long before they turn deadly.

That’s why stopping HPV isn’t about treating cancer-it’s about stopping it before it starts.

The Vaccine: A Simple Shield Against Cancer

The first HPV vaccine, Gardasil, was approved in 2006. Today, there are three vaccines on the market, all targeting the most dangerous strains. The current one used in the U.S., Gardasil 9, protects against nine types of HPV, including 16 and 18, and covers about 90% of cervical cancer cases.

The CDC recommends the vaccine for all kids at age 11 or 12. That’s not because they’re at risk of sexual activity-it’s because the immune response is strongest before exposure. The vaccine works best when given before any contact with HPV. But it’s not too late if you’re older. The vaccine is approved up to age 45. Even if you’ve had HPV before, the vaccine can still protect you from other strains you haven’t encountered.

Two doses are enough for those starting before age 15. For people starting at 15 or older, three doses are needed. The vaccine is safe. Side effects are mild-sore arm, headache, or dizziness. It doesn’t cause infertility, chronic pain, or autoimmune diseases. Those myths have been thoroughly debunked by studies involving millions of doses.

Real-world data shows the vaccine works. In Australia, where vaccination rates are over 80%, cervical precancers in young women dropped by 85% in just a decade. In the U.S., HPV infections in teen girls fell by 88% between 2006 and 2018.

Screening: Finding Problems Before They Become Cancer

Even if you’ve been vaccinated, you still need screening. The vaccine doesn’t protect against all cancer-causing HPV types. And not everyone gets vaccinated.

For years, the Pap test was the gold standard. It looks for abnormal cells in the cervix. But it’s not perfect. It misses a lot of early changes. Today, the best tool is the HPV test itself.

Primary HPV testing detects the virus before it causes cell changes. It’s more sensitive than the Pap test. A 2018 JAMA study found it caught 94.6% of serious precancers, compared to just 55.4% for Pap alone. That’s why major groups like the American Cancer Society and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force now recommend HPV testing as the main screening method.

Here’s what the current guidelines say:

- Ages 25-29: HPV test every 5 years (preferred), or Pap test every 3 years.

- Ages 30-65: HPV test every 5 years (best option), or Pap test every 3 years, or both together every 5 years.

- Over 65: No screening needed if you’ve had regular negative tests in the past.

The shift to HPV testing means longer intervals. Five years between tests is safe-safer than three-year Pap tests. A 2023 study showed that after two negative HPV tests, the risk of developing cervical cancer in the next six years was extremely low.

Self-Testing: Breaking Down Barriers

One of the biggest reasons people skip screening? Discomfort. Fear. Lack of access. Time. Transportation. For many, a pelvic exam feels invasive, embarrassing, or impossible to schedule.

Now, there’s a game-changer: self-collected HPV tests.

You can swab your own vagina at home using a simple kit. Studies show it’s just as accurate as a test done by a doctor. Kaiser Permanente started offering it in January 2024. In Australia and the Netherlands, self-testing boosted screening rates by 30-40% among women who hadn’t been screened in years.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force now supports self-collected HPV testing as a valid option. It removes one of the biggest barriers to care-especially for people in rural areas, those with disabilities, or those who’ve experienced trauma.

What Happens If Your Test Is Positive?

A positive HPV test doesn’t mean you have cancer. It just means the virus is present. Most of the time, it goes away on its own.

If you test positive for HPV 16 or 18, you’ll usually get a follow-up colposcopy-a quick exam where a doctor looks at your cervix with a magnifying tool. If you test positive for another high-risk type, you might get a Pap test to check for cell changes.

If precancer is found, it can be removed in a simple outpatient procedure. No hospital stay. No chemotherapy. Just a small tool to burn or cut away the abnormal tissue. It’s quick, safe, and nearly 100% effective at stopping cancer before it begins.

Why This Matters for Everyone

HPV doesn’t care about your income, race, or zip code. But access to prevention does.

In the U.S., Black women are 70% more likely to die from cervical cancer than White women. In low-income countries, only 19% of women have ever been screened. Meanwhile, in high-income nations, screening rates are over 80%.

The World Health Organization’s 90-70-90 goal by 2030 isn’t just a number. It’s a lifeline: 90% of girls vaccinated by 15, 70% of women screened by 35 and 45, and 90% of abnormal cases treated. If we hit these targets, we could prevent 62 to 77 million cervical cancer cases over the next century.

That’s not science fiction. It’s math. And it’s already working in places that made the investment.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re under 26: Get the HPV vaccine if you haven’t already. It’s one shot in a lifetime that can prevent cancer.

If you’re 25-65: Ask your provider about HPV testing. Don’t wait for a Pap test unless your provider says it’s right for you. Push for the more accurate option.

If you’ve avoided screening for years: Ask about self-testing. Many clinics now offer it. You can do it at home, in private, and send it in by mail.

If you’ve had the vaccine: Keep getting screened. Vaccination isn’t a pass to skip tests.

If you’re a parent: Talk to your child’s doctor about the vaccine. Don’t wait until they’re older. The earlier, the better.

HPV isn’t shameful. It’s common. And cancer from it? That’s not fate. It’s a failure of access, awareness, and action. We have the tools. We just need to use them.

What’s Next for HPV Prevention?

Research is moving fast. AI is now being used to read Pap smears with higher accuracy than human eyes. Paige.AI got FDA approval in early 2023 for its AI system that flags abnormal cells.

Some studies are testing whether six-year screening intervals are safe after two negative HPV tests. Early results look promising.

And global efforts are expanding. Countries like Rwanda have vaccinated over 90% of girls by age 15. Now they’re rolling out HPV self-testing nationwide.

The goal isn’t just to reduce cervical cancer. It’s to eliminate it as a public health threat by 2050. That’s possible. But only if we all do our part.

Do I still need screening if I got the HPV vaccine?

Yes. The HPV vaccine protects against the most common cancer-causing types, but not all of them. Screening catches other high-risk strains and catches changes early. Vaccination and screening work together-they’re not alternatives.

Can men get tested for HPV?

There’s no approved HPV test for men. But men can still benefit from the vaccine, which prevents genital warts and reduces the risk of anal, penile, and throat cancers. Vaccinating boys also helps protect future partners.

Is HPV only spread through sex?

HPV spreads through skin-to-skin contact during vaginal, anal, or oral sex. It can also spread through close genital contact without penetration. You don’t need to have multiple partners to get it. It’s so common that most sexually active people will get it at some point.

What if I’m over 45? Is it too late for the vaccine?

The vaccine is approved up to age 45. If you haven’t been exposed to all the strains it covers, it can still help. Talk to your doctor-especially if you’ve had new partners or haven’t been vaccinated before.

How accurate is self-collected HPV testing?

Studies show self-collected tests are nearly as accurate as clinician-collected ones. Sensitivity is around 84-85%, and specificity is over 90%. That’s good enough to catch precancerous changes early. Many health systems now accept self-tests as valid for screening.

Can HPV cause cancer in men?

Yes. HPV causes anal, penile, and oropharyngeal (throat) cancers in men. These cancers are rising, especially in men who have sex with men. The vaccine prevents these cancers too. Men should get vaccinated just like women.

Hi, I'm Caden Lockhart, a pharmaceutical expert with years of experience in the industry. My passion lies in researching and developing new medications, as well as educating others about their proper use and potential side effects. I enjoy writing articles on various diseases, health supplements, and the latest treatment options available. In my free time, I love going on hikes, perusing scientific journals, and capturing the world through my lens. Through my work, I strive to make a positive impact on patients' lives and contribute to the advancement of medical science.