When a patient picks up their prescription and walks out the door, most assume the generic pill in the bottle is just as good as the brand-name version. And for the vast majority of cases, it is. But not always. Pharmacists are on the front lines - the last checkpoint before a medication reaches a patient - and they need to know when to pause, question, and speak up. Not because generics are dangerous, but because some problem generics can slip through the cracks and cause real harm.

Why Generics Work - And When They Don’t

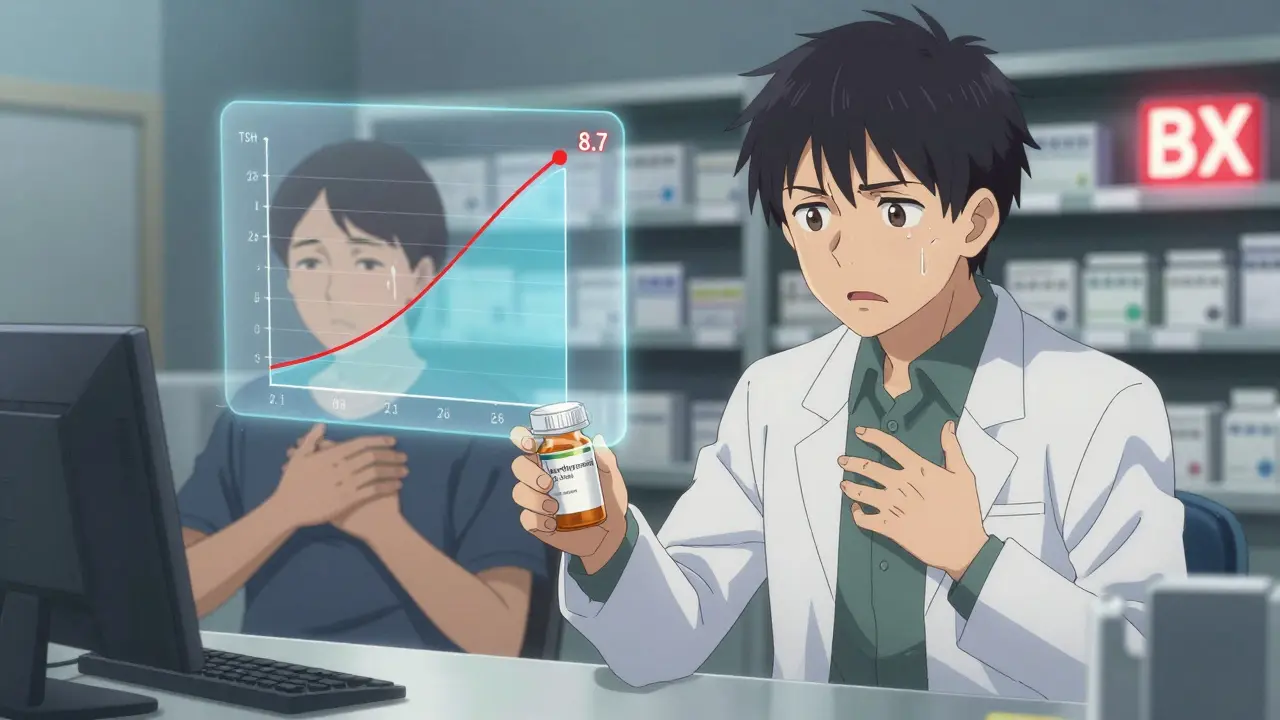

Generic drugs are supposed to be exact copies of brand-name drugs. Same active ingredient. Same dose. Same way of taking it. The FDA requires them to prove they work the same way in the body, with bioequivalence studies showing absorption levels within 80% to 125% of the original. That sounds tight. But here’s the catch: 20% variation is still allowed. For most drugs, that’s fine. For others? It’s dangerous. Take levothyroxine, the most common treatment for hypothyroidism. A patient stable on one generic manufacturer’s version might switch to another - maybe because the pharmacy changed suppliers or insurance pushed a cheaper option - and suddenly, their TSH levels spike. One case documented by a pharmacist in Florida saw a patient’s TSH jump from 2.1 to 8.7 in just six weeks. That’s not a fluke. Studies show switching generic brands of levothyroxine leads to therapeutic failure 2.3 times more often than with non-narrow therapeutic index drugs. The FDA calls these high-risk medications narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. There are 18 of them. Digoxin, warfarin, phenytoin, cyclosporine, tacrolimus - these aren’t just any pills. A tiny change in blood levels can mean the difference between control and catastrophe. A patient on warfarin might bleed internally. A transplant patient on tacrolimus could reject their new organ. These aren’t theoretical risks. They’re documented.When to Raise the Red Flag

Pharmacists don’t need to be drug detectives. But they do need to recognize patterns. Here are the top three red flags:- Therapeutic failure within 2-4 weeks of a generic switch. If a patient who was doing fine on a brand or one generic suddenly reports symptoms returning - seizures, chest pain, unexplained fatigue, weight gain - it’s not "just in their head." It’s likely the new generic.

- Unusual side effects after switching manufacturers. Nausea where there was none before. Dizziness. Skin rashes. These aren’t always allergic reactions. Sometimes, it’s a different inactive ingredient - the filler, the coating, the slow-release polymer - that’s causing the issue. Extended-release formulations are especially prone to this.

- Look-alike, sound-alike confusion. Oxycodone/acetaminophen vs. hydrocodone/acetaminophen. Clonazepam vs. clonidine. These names are dangerously close. A 2022 ISMP report found 14.3% of all generic medication errors came from this kind of mix-up. It’s not the active ingredient that’s wrong. It’s the label.

What Makes Some Generics Riskier Than Others

Not all generics are created equal. The FDA’s Orange Book rates them with codes. AB means "therapeutically equivalent." BX means "not therapeutically equivalent" - usually because bioequivalence data is incomplete or inconsistent. As of October 2023, over 10% of generic drugs carry that BX rating. The biggest troublemakers? Complex formulations. Extended-release tablets, transdermal patches, inhalers, injectables - these are hard to copy. The way the drug is released matters. A 2020 FDA study found that 7.2% of generic extended-release opioids failed dissolution testing. That means the pill didn’t release the drug the way it should. Some patients got too much too fast. Others got nothing at all. Diltiazem CD is one example. Between January 2021 and March 2022, the FDA received 47 reports of therapeutic failure from patients switched to a specific generic version. Some had angina flare-ups. Others developed low blood pressure. The problem? The generic’s coating didn’t dissolve at the same rate. The FDA issued a public warning. But how many pharmacists saw it?

What Pharmacists Can Do - Right Now

You don’t need a lab to catch a bad generic. You need awareness and a system.- Check the Orange Book. Every time you dispense a generic, glance at its therapeutic equivalence code. If it’s BX, don’t assume it’s safe. Ask: Is this the same manufacturer as before? Has the patient been stable?

- Document the manufacturer. Write the manufacturer name on the prescription or in the electronic record. If a patient reports a problem, you’ll need that info to trace it. A 2022 University of Florida study found 68.4% of therapeutic failure investigations required knowing the specific manufacturer.

- Ask the patient. Don’t wait for them to complain. After a switch, say: "Have you noticed any changes since you started this new pill?" Even if they say "no," keep an eye out. Sometimes, patients don’t connect symptoms to medication.

- Report it. Use the FDA’s MedWatch system. It takes 4.7 minutes. You’re not just helping your patient - you’re helping the next one. Pharmacist-reported incidents rose 18.3% in states with mandatory reporting.

The Bigger Picture: Cost vs. Safety

Generics saved the U.S. healthcare system over $300 billion in 2022. That’s real money. But cost shouldn’t be the only driver when NTI drugs are involved. States like Massachusetts and New York require pharmacists to get explicit patient consent before substituting generics for NTI drugs. Other states assume consent unless the patient says no. That’s risky. A 2023 Health Affairs study found that states with presumed consent laws had higher generic substitution rates - but lower rates for NTI drugs. Why? Because pharmacists in those states were more cautious. They knew the stakes. The FDA is trying to fix this. Their 2023 Drug Competition Action Plan targets complex generics. They’re increasing inspections. They’re testing more samples. They’re even testing AI tools to spot patterns in adverse event reports. But until those systems are fully in place, pharmacists are the safety net. You’re not just filling prescriptions. You’re preventing harm.

Real Stories, Not Just Stats

One pharmacist in Ohio noticed a patient on phenytoin kept having seizures after switching to a new generic. She called the prescriber. The doctor dismissed it: "It’s the same drug." She insisted on a blood level test. The phenytoin level dropped 40%. The patient was switched back. No more seizures. Another in Texas saw a patient’s INR spike after switching warfarin generics. The patient was on vacation. No lab nearby. She called the pharmacy’s clinical team. They coordinated with a local clinic. The patient avoided a stroke. These aren’t outliers. They’re routine.Final Thought: Trust, But Verify

The system works - most of the time. But when it doesn’t, the consequences are severe. Pharmacists aren’t here to second-guess every generic. They’re here to catch the ones that matter. If a patient’s condition changes after a switch - especially with NTI drugs - don’t brush it off. Don’t assume it’s compliance. Don’t assume the FDA’s stamp means perfection. Your job isn’t just to dispense. It’s to protect.What are narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs?

Narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs are medications where small changes in blood levels can lead to serious side effects or treatment failure. Examples include levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, digoxin, cyclosporine, and tacrolimus. The difference between an effective dose and a toxic one is very small, so even slight variations in generic formulations can have major clinical impacts.

Can generic drugs cause different side effects than brand-name drugs?

Yes. While the active ingredient is the same, inactive ingredients - like fillers, dyes, or coatings - can differ between manufacturers. These can affect how the drug is absorbed or how it interacts with the body. Patients have reported new or worsened side effects like nausea, dizziness, or rashes after switching generics, even if the active drug is unchanged.

How do I know if a generic is therapeutically equivalent?

Check the FDA’s Orange Book. Drugs rated "AB" are considered therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name version. Those rated "BX" are not - usually because bioequivalence data is incomplete or inconsistent. Pharmacists should always verify this code before dispensing, especially for NTI drugs.

Should I always ask for patient consent before switching to a generic?

In most states, pharmacists can substitute generics without explicit consent. But for NTI drugs, best practice is to inform the patient and document their preference. Some states - like Massachusetts and New York - require consent for NTI substitutions. Even if not required, asking builds trust and helps catch problems early.

What should I do if a patient reports a problem with a generic drug?

First, document the manufacturer name, batch number, and date of switch. Then, contact the prescriber to discuss alternatives. If appropriate, consider switching back to the previous version or a different generic. Report the incident to the FDA’s MedWatch system. Most importantly, don’t dismiss the patient’s experience - their symptoms are real, and your response can prevent harm.

Hi, I'm Caden Lockhart, a pharmaceutical expert with years of experience in the industry. My passion lies in researching and developing new medications, as well as educating others about their proper use and potential side effects. I enjoy writing articles on various diseases, health supplements, and the latest treatment options available. In my free time, I love going on hikes, perusing scientific journals, and capturing the world through my lens. Through my work, I strive to make a positive impact on patients' lives and contribute to the advancement of medical science.